I am huge believer in markets…clearly. I think that the market should set the price. By “market”, I mean the buyers.

You walk into a store and and there is a clearance section where the price of the item as been reduced, sometimes by a lot. Why? Because the buyers decided that they didn’t want those products at the original price. The store will continue to mark down the item until it reaches a price that attracts buyers. The same goes for real estate, set the price too high and there are usually no bids at that price after the open house that you hosted. However, there will usually be some bids at a lower price. The market just told the homeowner what the house is worth, at least in that current environment. The price of Apple’s stock is trading at $122.44 as I write this. That is the price where supply meets demand. You go on five job interviews for roles that you think match your skills currently and you receive three offers with a salary attached. They represent the price where the market is currently pricing your skills. We can do this all day but I think the point is pretty clear. This is fairly straight forward, Econ 101 concepts here. Remember this one?

However, there is one place where this dynamic does not hold, at least not in its truest form. The pricing of initial public offerings or IPOs. In the case of an IPO, a group of investment bankers work with the company to come up with a price range where they all think that the stock should trade for the first time. Then the bankers and the company embark on a roadshow where they travel the country (and sometimes the world) to tell the story and to drum up interest in the offering. They will meet hundreds of investors during this roadshow. Some meetings will be one to one, others will be in a group setting. Once the roadshow is over, the banks will reach out to all of the investors who have an interest in the company to see if they have an interest IPO and if so, how big of an interest. Then based on the level interest, the price may be adjusted higher or lower but it usually does not deviate too far from the original range.

Yesterday, I mentioned the last week’s two big IPOs. Doordash and Airbnb. I am not going to get into the merits of each company, that’s not the point. According to Fact Set, Doordash (DASH) ended the week up 72% from the $102 offering price and Airbnb (ABNB) leaped higher 108% from the $68 offering price following the IPOs of those companies this week. Airbnb was the 19th company this year to double in its first day of trading, the most since 2000. Bloomberg did a good job on the subject here. This begs the question, how could the deals be priced so badly. Clearly the initial price was wrong. The management teams of these companies should be furious due to the amount of money that was left on the table by these mispricings.

The IPO pricing process has always been a big pet peeve of mine. You see, while the bankers who work on these deals are extremely smart, many having gone to the some of the best school in the world for both undergrad and business school, for the most part they are not “market” people. I do not mean that as an insult. It is a different skill set. The bankers are great at studying businesses. They care about thinks like strategy and competition. Markets people care about the supply / demand dynamics that drive the price of an asset.

The other problem is that the banks who work on these deals are serving two sets of clients with diametrically opposed goals. The bank serves the company which is going public and wants the highest price the market will bring. At the same time, the institutional investors who buy the IPO (mutual funds and hedge funds) are also clients of the bank. These investors want to transact at the lowest price possible. How do you square this issue? Because there is clearly an issue.

Many will say that there is nothing that can be done or this is how it is done. But I pushback. Some will say that the best idea is to cut the bank out and have the company sell stock directly to investors. This may work for very high profile companies but what about the lesser known companies? The banks do serve an important role of getting the deal in front of as many investors as possible. We have all heard of Airbnb but have you ever heard of Upstart Holdings? No? They are going public this week and the teams at the banks are likely working hard to make sure the right investors know the story. So banks do serve a critical purpose on the majority of these offerings.

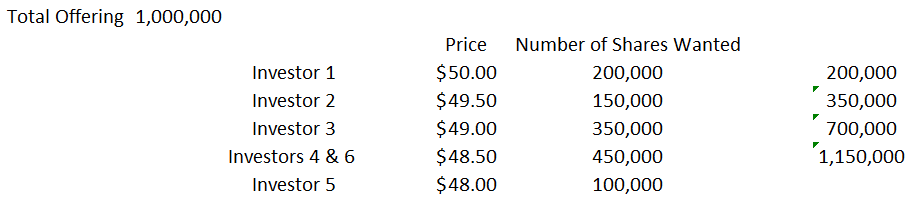

I think the best way is the Dutch Auction. A Dutch auction is a public offering auction structure in which the price of the offering is set after taking in all bids to determine the highest price at which the total offering can be sold. The banks can set up their meetings and run the roadshow, completing all of the most important tasks that banks handle in this process. But then when it comes time to price the deal, let the investors take control. In this type of auction, investors place a bid for the amount they are willing to buy in terms of quantity and price. Here is a quick example. Let’s assume that XYZ Co wants to sell one million shares of its stock to the public. After all the roadshow meetings, the order book looks like this:

Once all the bids are submitted, the allotted placement is assigned to the bidders from the highest bids down, until all of the allotted shares are assigned. However, the price that each bidder pays is based on the lowest price of all the allotted bidders, or essentially the last successful bid. In our example, the IPO would price at $48, which is where demand equals the one million share supply. Investors 1 - 5 would all buy the amount of stock that they want and Investor 6 would get nothing. The “market” has set the price and the banks have served their key role by getting the company in front of the right investors with the right information so that the deal could be completed.

This process can also work to get a higher price for the deal The banks remain in constant contact with the investors. Perhaps, through subsequent conversations with the people at the bank who know the offering company well and after doing more research on their own, Investor 6 decides to step up to $48.50 along with Investor 4. Here is what the book looks like now:

The offering would now be priced at $48.50, where there is actually excess demand. The “market” has still set the price but the bank’s hard work yielded an extra $0.50 / share for the company. This just makes sense to me. Price is set by the intersection of supply and demand. By the way, Google went public in this way.

PS: The gaming company Roblox was set to go public before the end of the year. Both of my daughters love the games and I was looking forward to showing them how the stock traded and maybe even buying a few shares for each of them so that they can follow along with something that interests them. Roblox postponed the offering until next year. It is speculated that part of the reason is so that they can get the pricing right. Translation: they want to make sure it prices so that they get a higher price and not leave a large sum on the table the way DASH and ABNB did.